|

|

Chris De Herrera's Windows CE Website |

|---|---|

About |

|

| By Chris De Herrera Copyright 1998-2007 All Rights Reserved A member of the Talksites Family of Websites Windows and

Windows CE are trademarks of

Microsoft All Trademarks are owned |

Guide to Writing

Pocket PC Game Reviews

By

Allen Gall, Copyright 2002

Revised 5/9/2002

Allen is available for freelance writing projects

involving Pocket PC software and hardware, everything ranging from press

releases to documentation. If you have a project,

e-mail me and we'll chat.

[an error occurred while processing this directive]

So you've been thinking about becoming a reviewer? Or just wanting to spread the word on that new game that's draining your batteries like crazy? Or maybe you just bought a really good (or really bad) game and want to share your experience with the world. If you want to go into a little more depth than you can on a message board, there’s always the game review. There was a time when print publications were all there was, and one had to be a fairly competent writer to even compete for space in one of them. But in the mid-90s, fan Web sites catering to gamers began popping up like crazy, featuring amateur reviews written by fanatics that made up for whatever they may have lacked in writing ability in attitude and insider savvy. While uneven in quality, amateur reviews often have a tell-it-like-it-is earnestness that more polished reviews tend to lack.

Gamers, as any developer will tell you, are an incredibly finicky bunch.

(Remember the original  Tomb

Raider on the desktop PC? The first game was

smokin',

but by the third incarnation, it was a

dead fish.)

Sometimes, word of mouth is enough to make or break a game.

Recognizing the potential in grass-roots marketing, game developers in the

mid-90s started to provide review copies to everything from legit sites to

IRC-based newsletters like

The Game Review,

never mind that the latter consisted of short, snippy paragraphs written by

software pirates for other pirates (Pirates are a finicky bunch; after all,

downloading a bad game means either a wasted CD or having to hit the delete

key).

Tomb

Raider on the desktop PC? The first game was

smokin',

but by the third incarnation, it was a

dead fish.)

Sometimes, word of mouth is enough to make or break a game.

Recognizing the potential in grass-roots marketing, game developers in the

mid-90s started to provide review copies to everything from legit sites to

IRC-based newsletters like

The Game Review,

never mind that the latter consisted of short, snippy paragraphs written by

software pirates for other pirates (Pirates are a finicky bunch; after all,

downloading a bad game means either a wasted CD or having to hit the delete

key).

Fortunately, PDA gamers have lots of venues to write reviews. Amateur reviews are, after all, the backbone of the gaming scene, since the mainstream gaming press still has a pretty limited interest in PDA gaming. Since the PDA gaming market is still a niche within a niche, that won't change anytime soon. Still, more reviews are a good thing, and they seem to be getting more popular as the games themselves become more numerous.

What follows are some of my thoughts on what a good game review should contain. This isn't an exhaustive list, nor a definitive one; just some of my opinions as well as observations I've made that should help those of you thinking about writing reviews.

1.

Know what a review is.

A review is just that--an analysis, an evaluation, a commentary. It is

not a list of features, nor is it an extended press release. The

descriptive parts of a review (features, bugs, requirements, etc.) are nice

to have in a review, but they shouldn't dominate it. You'll have to do

some describing, of course, for the reader to know what you’re

talking about. But, the descriptive parts should just provide an

overview and should largely support your opinions. After all, feature

lists about a particular product can be obtained from a variety of sources.

You should also keep the instructive parts (how to play the game, how to

install it, etc.) fairly brief, and their purpose should also be to support

your opinions. For example, if you're reviewing a

Hexacto

sports title, you'd probably want to give a concise overview of the

controls (Hexacto uses a fairly sophisticated input method in some of their

sports titles) to comment on how well they work. If there are any

weaknesses (Did you have trouble performing any tasks?), discuss them with

an eye toward quality of implementation and overall functionality.

Remember that you're not out to teach the player how to play the

game--that's for the game documentation (it's OK to give a hint or two).

Your job is to provide an assessment.

1.

Know what a review is.

A review is just that--an analysis, an evaluation, a commentary. It is

not a list of features, nor is it an extended press release. The

descriptive parts of a review (features, bugs, requirements, etc.) are nice

to have in a review, but they shouldn't dominate it. You'll have to do

some describing, of course, for the reader to know what you’re

talking about. But, the descriptive parts should just provide an

overview and should largely support your opinions. After all, feature

lists about a particular product can be obtained from a variety of sources.

You should also keep the instructive parts (how to play the game, how to

install it, etc.) fairly brief, and their purpose should also be to support

your opinions. For example, if you're reviewing a

Hexacto

sports title, you'd probably want to give a concise overview of the

controls (Hexacto uses a fairly sophisticated input method in some of their

sports titles) to comment on how well they work. If there are any

weaknesses (Did you have trouble performing any tasks?), discuss them with

an eye toward quality of implementation and overall functionality.

Remember that you're not out to teach the player how to play the

game--that's for the game documentation (it's OK to give a hint or two).

Your job is to provide an assessment.

After reading your review, the reader should know what kind of game you're talking about and what you think of it. They should know what you liked about it, what you didn't, and, most importantly, why. From that, they should be able to determine if they're interested in downloading a demo of the game or making a purchase.

A review is not meant to sell a product, nor is it meant to function as a press release. Quite often, I get sent press releases, download links to demos, and review copies. This is fine, and I welcome it--it makes my job easier. A while back, an Asian company launched a campaign where they offered to give registered copies of their new game to reviewers willing to write a review of their new title. I refused to participate in this offer because I felt it would encourage people to write reviews--ostensibly positive reviews--in order to get a free game. Sure, a review--especially a positive one--can help sell games, and many game developers send copies to people in the press hoping to get some exposure with a positive review. Your goal in writing a review should be to let your fellow gamers know about a game and what makes it good or bad. Remember that a bad review shouldn't necessarily "trash" a weaker product; it should just point out the flaws in. We want to support quality titles and help improve weaker ones so that developers will make the kinds of games we want to buy.

2. What to include. Of course, this is going to vary. Some reviewers like to focus on a specific aspect of a game. Others go for a more balanced approach. In general, your review should at least mention the following aspects:

1. Graphics - People have varying opinions on how important this is,

but there's no denying that what the game looks like is a factor in how

enjoyable it is. It's understood that most

puzzle

games aren't going to have state-of-the art graphics, but there at least

should attention to creating a visually appealing experience. In newer

action and arcade games, graphics become more important, since such games

are indirectly competing with powerful consoles and coin-op machines.

In adventure games, they draw you into the game's mythos and story (assuming

there is one). In simulations (sports, driving, flying, etc.)

they make the action more believable and therefore more enjoyable.

What kind of graphics does the game use? Tile-based? Sprites?

3D models? Graphics can't make a bad game good, but they can really

show off the appeal of a good game.

puzzle

games aren't going to have state-of-the art graphics, but there at least

should attention to creating a visually appealing experience. In newer

action and arcade games, graphics become more important, since such games

are indirectly competing with powerful consoles and coin-op machines.

In adventure games, they draw you into the game's mythos and story (assuming

there is one). In simulations (sports, driving, flying, etc.)

they make the action more believable and therefore more enjoyable.

What kind of graphics does the game use? Tile-based? Sprites?

3D models? Graphics can't make a bad game good, but they can really

show off the appeal of a good game.

2.

Sound - Sound is essential in gaming. The early Intel-based PC was a

pretty crappy gaming platform until the first sound cards made their debut

in the late 1980s (Anyone besides me remember the SoundBlaster 1.5?)

Current Pocket PC models come with 16-bit stereo sound capability.

Sound is going to be more important in action/arcade games than in card or

puzzle games, but there’s really no excuse for silence. Auditory

output gives a much-needed additional dimension to what's being displayed on

the screen. It makes the player feel they have a stake in what's going

on, and it provides a satisfying extra layer of feedback, whether it's the

rev of the engine in a racing game, the sound of a weapon being fired in a

“shooter,”

or the click of a piece falling down in a puzzle game. How good are

the sounds? Do they sound tinny? Or are they overdone (too loud,

too quiet, too deep, etc.)? Music, on the other hand, helps set the

mood for the game. In

Argentum,

the music did a good job of setting a tone of seriousness and helped build

suspense. Just as carefully selected and placed music can

pull you into a movie,

it can also draw you a little deeper into a game. In general, the

music should match the genre of the game. Music generally highlights

the type of game play involved: puzzle and action games usually have upbeat,

quick-tempo numbers with repetitive rhythms. Adventure and strategy

games will have much more dramatic music, especially if the story involves

saving the world from evil aliens, evil humans, exploring a haunted house,

and so forth.

2.

Sound - Sound is essential in gaming. The early Intel-based PC was a

pretty crappy gaming platform until the first sound cards made their debut

in the late 1980s (Anyone besides me remember the SoundBlaster 1.5?)

Current Pocket PC models come with 16-bit stereo sound capability.

Sound is going to be more important in action/arcade games than in card or

puzzle games, but there’s really no excuse for silence. Auditory

output gives a much-needed additional dimension to what's being displayed on

the screen. It makes the player feel they have a stake in what's going

on, and it provides a satisfying extra layer of feedback, whether it's the

rev of the engine in a racing game, the sound of a weapon being fired in a

“shooter,”

or the click of a piece falling down in a puzzle game. How good are

the sounds? Do they sound tinny? Or are they overdone (too loud,

too quiet, too deep, etc.)? Music, on the other hand, helps set the

mood for the game. In

Argentum,

the music did a good job of setting a tone of seriousness and helped build

suspense. Just as carefully selected and placed music can

pull you into a movie,

it can also draw you a little deeper into a game. In general, the

music should match the genre of the game. Music generally highlights

the type of game play involved: puzzle and action games usually have upbeat,

quick-tempo numbers with repetitive rhythms. Adventure and strategy

games will have much more dramatic music, especially if the story involves

saving the world from evil aliens, evil humans, exploring a haunted house,

and so forth.

3.

Interface/controls - Obviously, the way the player interacts with the game

is an important aspect to consider when writing a review. The

interface defines how the player performs game tasks in most games (setting

options, creating a character, starting levels, purchasing upgrades, etc.)

In general, the interface should be intuitive and simple. In titles

like

SimCity 2000

and

Lemonade, Inc.,

which consist of tapping icons and navigating menus, the interface and game

controls are effectively the same. In action games, they can be

separate. Ideally, controls should be responsive, intuitive, and

should allow the player to focus on interacting with the game rather than

3.

Interface/controls - Obviously, the way the player interacts with the game

is an important aspect to consider when writing a review. The

interface defines how the player performs game tasks in most games (setting

options, creating a character, starting levels, purchasing upgrades, etc.)

In general, the interface should be intuitive and simple. In titles

like

SimCity 2000

and

Lemonade, Inc.,

which consist of tapping icons and navigating menus, the interface and game

controls are effectively the same. In action games, they can be

separate. Ideally, controls should be responsive, intuitive, and

should allow the player to focus on interacting with the game rather than

![]()

![]()

getting into a struggle with stylus and buttons. With the variety of devices available, control methods are going to vary, so having them customizable is a definite plus. If the game uses an unusual control method (either good or bad), it's probably worth discussing. A good control scheme allows you to focus on what's going on in the game so that you don't have to think about what button you need to push next if you're approaching a door or if you need to shift gears when going around a curve. When the original iPaq came out, it fairly quickly became the dominant device in spite of one crippling limitation: the device couldn’t accept simultaneous button presses. Developers therefore had to circummvent this limitation by accepting input through the stylus. Today, however, most models have a built-in d-pad and can accept multiple button presses just fine. The functionality of the controls is something to consider when writing your review (it can impact game play, something we’ll talk about in a bit).

4. Design

- This is a more encompassing term and includes such things as type of game,

control method, level progression and design, player options (including what

they’re allowed and not allowed to do), various game options and settings,

and other factors. In a sense, it determines what the player will do

in the game. Simple games like

Bejeweled

have simple design elements, requiring the player to swap objects in order

to make matches, usually offering two or more game modes featuring  progressively

difficult levels. Games like RPGs have more complex design, since it's

necessary to first determine how the character will be allowed to develop

through level progression, then throw progressively difficult challenges at

the player that will also advance the game's storyline. In

Pocket EverQuest,

for example, designers chose the character classes, available spells,

skills, bonuses, and the various quests the player would go on. They

also had to determine how the various character types would go about

completing each quest. One trend starting to appear in games is the

have-it-your-way approach, which allows the player to choose the type of

game play. The racing game

Gangsta Race

lets the player prgress through the levels in one of three modes, one which

ofers combat, one which offers straight racing, and another in which the

main goal is simply to survive.

Hyperspace Delivery Boy

provides a similar option—although the game is primarily puzzle based,

players can choose from one of two game play modes in dealing with the

game’s monsters, one of which requires combat, the other requiring stealth.

Although you may not talk about design directly, it will have an impact on

game play.

progressively

difficult levels. Games like RPGs have more complex design, since it's

necessary to first determine how the character will be allowed to develop

through level progression, then throw progressively difficult challenges at

the player that will also advance the game's storyline. In

Pocket EverQuest,

for example, designers chose the character classes, available spells,

skills, bonuses, and the various quests the player would go on. They

also had to determine how the various character types would go about

completing each quest. One trend starting to appear in games is the

have-it-your-way approach, which allows the player to choose the type of

game play. The racing game

Gangsta Race

lets the player prgress through the levels in one of three modes, one which

ofers combat, one which offers straight racing, and another in which the

main goal is simply to survive.

Hyperspace Delivery Boy

provides a similar option—although the game is primarily puzzle based,

players can choose from one of two game play modes in dealing with the

game’s monsters, one of which requires combat, the other requiring stealth.

Although you may not talk about design directly, it will have an impact on

game play.

5. Game Play - Speaking of game play… this element is a little more inclusive and therefore more abstract. It's also frequently misunderstood. It doesn't just refer to how well the controls work or how the levels are designed. UnrealWiki (Don't ask me what that is-I have no idea) offers these two axioms:

1. The ability to interact with the (computer) game without concious effort in a manner that is both satisfying and enjoyable. – EntropicLqd

2. The resultant interaction of imagination between a collective of entities on a linear basis – be they a human player, or a form of Artifical Intelligence. - DJPaul

Both of these are interesting, but don't quite capture the big picture. The first is a bit too vague, the second a bit too nebulous. I'm including game play last because I'm of the opinion that it involves such things as sound, graphics, interface, performance, controls, and other factors. I would define it as this:

Game play is the ability of the software to minimize the natural barriers between program and player. It is the ability of all its elements (controls, graphics, sound, design, etc.) to come together, allowing the player to be willing and able to accept and accommodate the rules, philosophy, and limitations of the game environment. Ultimately, it is the ability to accept the game on its own terms, and, for a short time, suspend disbelief and become part of its world, disregarding all external distractions.

Essentially, game play is a holistic term relating to the overall ability of the game to engage the player, and make him or her want to make the blocks connect, make the aliens die, fly the airplane or drive the car, and explore the dungeon, essentially becoming the in-game person.

We've all played games with really good game play (the ones that make us miss meetings, arrive late at school, and stay up way too late), and games where it wasn't there, i.e., games we “just couldn't get into.” In order to like a book or movie you have to like the characters or at least what's happening to them, and in order to like a game you have to care at least a little about what the game is asking you to do. Most of us are willing to overlook the other elements of a game if they're less than ideal, but a game without strong game play just isn't a game.

3. Keep it organized. Ideally, a review should have three parts:

Intro - This is where you introduce the game. At the least, you should have the title and

author/publisher. You should give some context for the game--is it a majorly awaited release? A surprising title by a lesser-known author? Part of a series?

Body-here's where you'll develop your analysis of the game. The approach you take depends mainly on your style. I would avoid the narrative approach (I downloaded the game, installed it on my device, etc.) unless there's something specific about the process you want to discuss. Remember to focus on your impressions of the game (keeping it analytical rather than descriptive) while backing up your opinions of strengths and weaknesses with specifics.

Conclusion--the part where you wrap it all up. This shouldn't just reiterate your intro; it should make some general conclusions based on the body of the review. Try to look at the game as a whole. You should tell readers if it's fun, and, more than anything, if it's worth their time. How original is it? How does it stack up against the competition? Readers should be able to read your conclusion and get a concise snapshot of how you feel about the game.

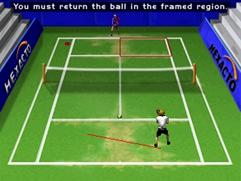

4. Include screenshots. As anyone who's tried to write a review can attest, it's hard to describe visual media such as software (particularly games) with words. Screen shots can help here, but don't include so many that they break up the narrative of your review and you end up simply writing around them. If you want to include many (more than two) screenshots, place them outside the review itself. Remember that screenshots should highlight your review, not dominate it. For shots placed within the text, include a brief descriptive caption. Studies have indicated that many people will scan a review for, reading only the screenshots and captions, to detemine if they want to actually read the review itself. It's usually good to include the title and want you want the reader to notice about the screenshot. If you can, place the screenshot in a place that makes sense. For example, if your shot is meant to show the quality of the graphics, place it near the part of the review where you discuss graphics.

5. Ask for a review copy if necessary. Getting free games is a perk of being a reviewer. However, it isn’t always necessary—sometimes a demo is enough to give an evaluation of a game, especially if the demo provides the full range of options available to the gamer. When soliciting a review copy, remember to give your full name and provide any credentials you might have and be prepared to back them up. Sometimes, companies like to verify identities to prevent people from pretending to be members of the press in order to get full copies (it does happen). If you’re courteous, most game companies will be happy to provide you with a review copy. Also, if you’re not sure if the review will be published, don’t make promises you can’t keep. If you provide a link to your review after it’s published, the company may remember you and send you additional releases to review when they become available.

6.

Include some sort of evaluative ranking.

This isn't essential, and I just started doing it myself. But it can

be very helpful. Basically, attaching a ranking to your review boils

it down to a letter grade or a number. Sometimes these rankings can be

fairly elaborate and even

convoluted

(some are given numbers down to a tenth of a point), consisting of a

breakdown of individual factors like "playability" and "fun factor" and

assigned a composite score based on the overall quality of the game.

Other times, the can be simple and even silly. I like the “letter”

grade system because a. It’s something everyone’s familiar with; b. It’s

very simple to use and read; c. People are expecting it these days on

everything from investments to video games to movies. Evaluative

rankings are good because, like thumbs-up, thumbs-down movie reviews, they

provide a quick-and-dirty assessment of a game. Many readers like this

because they can just go by the number, and some use it to determine if they

even need to read the review. if you decide to include such a ranking,

keep it simple. I don’t think the ratings system for most Pocket PC

applications (games or otherwise) needs to be sophisticated; the programs

are not quite complex enough, and there really aren’t enough competing

products to warrant such sophistication.

6.

Include some sort of evaluative ranking.

This isn't essential, and I just started doing it myself. But it can

be very helpful. Basically, attaching a ranking to your review boils

it down to a letter grade or a number. Sometimes these rankings can be

fairly elaborate and even

convoluted

(some are given numbers down to a tenth of a point), consisting of a

breakdown of individual factors like "playability" and "fun factor" and

assigned a composite score based on the overall quality of the game.

Other times, the can be simple and even silly. I like the “letter”

grade system because a. It’s something everyone’s familiar with; b. It’s

very simple to use and read; c. People are expecting it these days on

everything from investments to video games to movies. Evaluative

rankings are good because, like thumbs-up, thumbs-down movie reviews, they

provide a quick-and-dirty assessment of a game. Many readers like this

because they can just go by the number, and some use it to determine if they

even need to read the review. if you decide to include such a ranking,

keep it simple. I don’t think the ratings system for most Pocket PC

applications (games or otherwise) needs to be sophisticated; the programs

are not quite complex enough, and there really aren’t enough competing

products to warrant such sophistication.

Allen Gall is a freelance game reviewer and the games editor for CEWindows.NET. If you have a game you'd like Allen to review, you can e-mail him at allen@cewindows.net

[an error occurred while processing this directive]